Part 1 - 1894 to 1929

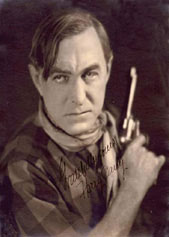

Ford was born John Martin “Jack” Feeney on February 1, 1894, in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, U.S.A.

Ford was born John Martin “Jack” Feeney on February 1, 1894, in Cape Elizabeth, Maine, U.S.A.

He grew up as the youngest in a tightly knit family, with Irish Catholic immigrant parents, speaking only Gaelic at home and learning English from his older siblings, and at school.

He followed an elder brother Francis, to Hollywood and there his stellar career began. His brother Francis took the last name of “Ford” in Hollywood as it was more Anglo-Saxon than, and not as Irish as Feeney. There was still a good deal of Irish prejudice in the United States in the early 20th Century. Young “Jack” Feeney decided he too would adopt the last name Ford.

At the Ince Studio, Epoch Film Corp. and the newly formed Universal Studios, “Jack” Ford worked as a general dogsbody, doing what he was told, working as a prop-man, assistant director, stuntman, bit actor. He was learning the movie business from the ground up, all facets in the art and craft of making movies.

1914

- Lucille Love – The Girl of Mystery (production assistant, propman & stuntman)

- The Mysterious Rose (appeared in)

1915

- The Birth of a Nation (appeared in as a hooded klansman – lost his glasses under the hood, fell off his horse and thus drew the attention of the film’s director, D.W. Griffith)

- Three Bad Men and a Girl (appeared in)

- Hidden City (appeared in)

- The Doorway of Destruction (actor, assistant director)

- The Broken Coin (actor, assistant director)

- The Campbells Are Coming (appeared in)

1916

- Lumber Yard Gang (appeared in)

- Strong Arm Squad (appeared in)

- The Adventures of Peg O’ the Ring (actor)

- Chicken Hearted Jim (appeared in)

- A Bandit’s Wager (appeared in)

There are several versions of how “Jack” Ford made the jump to the ranks of director. The most likely version is in Ford’s own words, “At Universal I was pressed into service as a prop director, using a camera without film, to impress Carl Laemmle (founder and owner of Universal Studios), who had suddenly appeared from New York. I was just the prop boy, but I told the cowboys (actors in the film) to go down to the end of the street and come back toward the camera riding fast and yelling like hell. Laemmle came up with his entourage and I had the cowboys do their stuff. Laemmle seemed to like it. I improvised some more action, even having some of the cowboys fall off their horse on cue. A little later they needed a director for a two-reeler and Laemmle said, ‘Try Ford. He yells loud.’”

1917

- The Tornado (director, acted in, writer)

- Trail of Hate (director, appeared in)

- The Scrapper (director, acted in, writer)

- The Soul Herder (director)

Jack Ford’s close association with actor Harry Carey, through his brother Frank, raised his profile at Universal. The first Ford-Carey collaboration was called The Soul Herder. Ford and Carey fell into an easy working rhythm, and Ford watched the older man work, noted the economy with which he got his effects. “I learned a great deal from Harry,” remembered Ford. “He was a slow-moving actor when he was afoot. You could read his mind, peer into his eyes and see him think. These films we made together weren’t shoot-em-ups,” said Ford of these early pictures, in which Carey usually played a modest, shambling saddle tramp rather than a bold gunfighter. “They were character stories. Carey was a great actor…he always wore a dirty blue shirt and an old vest, patched overalls, very seldom carried a gun – and he didn’t own a hat! On each picture, the cowboys would line up and he’d go down the line and finally pick one of their hats and wear that. It would please the owner because it meant he worked all through that picture…”

Jack Ford’s close association with actor Harry Carey, through his brother Frank, raised his profile at Universal. The first Ford-Carey collaboration was called The Soul Herder. Ford and Carey fell into an easy working rhythm, and Ford watched the older man work, noted the economy with which he got his effects. “I learned a great deal from Harry,” remembered Ford. “He was a slow-moving actor when he was afoot. You could read his mind, peer into his eyes and see him think. These films we made together weren’t shoot-em-ups,” said Ford of these early pictures, in which Carey usually played a modest, shambling saddle tramp rather than a bold gunfighter. “They were character stories. Carey was a great actor…he always wore a dirty blue shirt and an old vest, patched overalls, very seldom carried a gun – and he didn’t own a hat! On each picture, the cowboys would line up and he’d go down the line and finally pick one of their hats and wear that. It would please the owner because it meant he worked all through that picture…”

- Cheyenne’s Pal (director, writer)

- Straight Shooting (first feature-length film) (director)

Ford’s first feature is also his earliest surviving complete film. Straight Shooting shows that Ford had already developed components of his great talent, specifically his gift for landscape. The compositions, usually in deep focus, have balance, depth and spaciousness, and he easily constructs all sorts of natural frames out of a tree and some foreground bushes. Interior sets were built in real locations so authentic exteriors can be glimpsed through windows and doorways.

Ford’s first feature is also his earliest surviving complete film. Straight Shooting shows that Ford had already developed components of his great talent, specifically his gift for landscape. The compositions, usually in deep focus, have balance, depth and spaciousness, and he easily constructs all sorts of natural frames out of a tree and some foreground bushes. Interior sets were built in real locations so authentic exteriors can be glimpsed through windows and doorways.

- The Secret Man (director)

- A Marked Man (director)

- Bucking Broadway (director)

- The Purple Mask (director, acted in)

1918

- The Phantom Riders (director)

- Wild Women (director)

- Thieves’ Gold (director)

- The Scarlet Drop (director, writer)

- Hell Bent (director, writer)

- A Woman’s Fool (director)

- Three Mounted Men (director)

1919

- Roped (director)

- The Fighting Brothers (director)

- A Fight for Love (director)

- By Indian Post (director)

- The Rustlers (director)

- Bare Fists (director)

- Gun Law (director)

- The Gun Packer (director, writer)

- Riders of Vengeance (director, writer)

- The Last Outlaw (director)

- The Outcasts of Poker Flats (director)

- Ace of the Saddle (director)

- Rider of the Law (director)

- A Gun Fightin’ Gentleman (director, writer)

- Marked Men (director)

Jack Ford was restless. He wanted to show the world he could do more than direct Harry Carey Westerns. And he wanted to earn more than $150 a week. That was all he was making by the summer of 1919, the most prolific year of his career. Carey, whom Ford had made into a major star, was earning fifteen times that amount, $2,250 a week.

Ford’s deal with Universal came up for renewal that September, shortly before he reached what he considered the artistic apogee of the Cheyenne Harry series with Marked Men. Universal doubled his weekly salary and early in 1920, let Ford make his first film set entirely outside the Western genre, The Prince of Avenue A. The star was the former heavyweight boxing champion James J. “Gentleman Jim” Corbett. The story dealt with Irish immigrant politics in a lightly entertaining fashion. The film was a success and John Ford had proved his versatility.

1920

- The Prince of Avenue A (director)

- The Girl in Number 29 (director)

- Hitchin’ Posts (director)

- Under Sentence (writer)

- Just Pals (director)

It was time to move. In December of 1920, Jack Ford left Universal and went to work for William Fox at Fox Film Corp.

It was not the only change in his life in the year 1920. Earlier that spring, at a St. Patrick’s Day dance thrown by Rex Ingram (the director of The Four Horseman of the Apocalypse) at the Hollywood Hotel, Jack met Mary McBryde Smith. Mary, a trained nurse, had come from New Jersey to visit her brother Wingate. She had little interest in movie-making, but a big interest in the skinny young man, six feet tall, with lots of deep red hair and a magnificent sense of humour.

Jack Ford and Mary were married July 3, 1920, with Irving Thalberg and William K. Howard as witnesses.

1921

- The Big Punch (director, writer)

- The Freeze-out (director)

- The Wallop (director)

- Desperate Trails (director)

- Action (director)

- Sure Fire (director)

- Jackie (director)

1922

- Nero (second unit director – uncredited)

- Little Miss Smiles (director)

- Silver Wings (co-director with Edwin Carewe)

- The Village Blacksmith (director)

1923

- The Face on the Barroom Floor (director)

- Three Jumps Ahead (director, writer)

- Cameo Kirby (director)

Ford continued his ascent at Fox with Cameo Kirby, a prestigious adaptation of a play by the popular Booth Tarkington. Although the only apparent print is in tatters, enough visual glory remains – a horseback chase through the pastures of the South, a pistol duel amidst tall grasses. Ford’s command of exteriors is leagues ahead of the interiors. It was with Cameo Kirby that Ford felt dignity creeping up on him. Although his friends would call him Jack for the rest of his life, for public consumption his billing was no longer Jack Ford. From Cameo Kirby on, he was to be professionally known as John Ford.

- North of Hudson’s Bay (director)

- Hoodman Blind (director)

1924

- The Iron Horse (producer, director)

In 1923, Paramount had an unexpected blockbuster with The Covered Wagon. This film fired the starting gun for the Western epic. William Fox was determined to try to top it. If The Covered Wagon told of the courage and hardships of pioneers of the late 1840s, then Fox would make a film about the post-Civil War building of the transcontinental railroad, which rendered such wagon trains obsolete.

In 1923, Paramount had an unexpected blockbuster with The Covered Wagon. This film fired the starting gun for the Western epic. William Fox was determined to try to top it. If The Covered Wagon told of the courage and hardships of pioneers of the late 1840s, then Fox would make a film about the post-Civil War building of the transcontinental railroad, which rendered such wagon trains obsolete.

Ford campaigned hard for the assignment. Although still a young man, Ford had massed a considerable body of experience. When he undertook The Iron Horse, he was only thirty-one years old, but he had directed dozens of two-reelers and over thirty-five features.

The majority of the filming was done at Dodge, Nevada, where the temperature was 20 below zero with snow. The crew slept on a circus train that was brought up on-site, and constructed the frontier town set that would figure in the story. They laid about a mile and a half of railroad track, and used only two real engines.

Ford staged the re-creation of the driving of the Golden Spike, with the original Jupiter locomotive, lent by the Central Pacific, and a twin of the original Union Pacific engine. “We stood and watched these two ancient engines move slowly toward each other,” reported one of the crew, “and finally touch over the last tie and golden spike.”

Ford would play out the theme of The Iron Horse – the conflict between the wilderness and civilization many times over the years. With The Iron Horse Ford created his first masterpiece, and staked out his territory as America’s tribal poet.

- Hearts of Oak (director)

1925

- Lightnin’ (director)

- Kentucky Pride (director)

- The Fighting Heart (director)

- Thank You (director)

1926

- The Shamrock Handicap (director)

- 3 Bad Men (director, writer)

- The Blue Eagle (director)

1927

- Upstream (director)

- 7th Heaven (second unit director, uncredited)

Ford remained a good soldier, willing to step in and help out as his employers deemed necessary. Frank Borzage was as skilled an emotional director as anybody in Hollywood, but he was not regarded as being talented with action, so Ford was called in to shoot scenes of the troop mobilization in 7th Heaven.

- What Price Glory (second unit director, uncredited)

1928

- Mother Machree (director)

- Four Sons (director)

- Hangman’s House (director)

As the silent era drew to its premature close, Ford made one of his best, most elaborate pictures. Hangman’s House is a little gem, moodily expressionist, a tribute to the great director Murnau whom Ford greatly admired.

As the silent era drew to its premature close, Ford made one of his best, most elaborate pictures. Hangman’s House is a little gem, moodily expressionist, a tribute to the great director Murnau whom Ford greatly admired.

The movie is based on a novel by Donn Byrne, a popular Irish novelist of the period, whose forward to the novel echoed Ford’s own feelings about Ireland: “I am certain that no race has for its home the intense love we Irish have for Ireland,” wrote Byrne. “It is more than love. It is passion. We make no secret of it.”

Variety raved that “the locale and characters are treated in a fine literary way and the scenic backgrounds…are remarkable for their pictorial beauty, so much so that the photographic quality of the whole production is one of its outstanding merits…from start to finish, the pictorial side of the production is a revelation of camera possibilities.”

- Napoleon’s Barber (director, first talkie)

- Riley The Cop (director)

1929

- Strong Boy (director)

- The Black Watch (co-directed with Lumsden Hare)

- Salute (director)

- Big Time (acted in)